Introduction

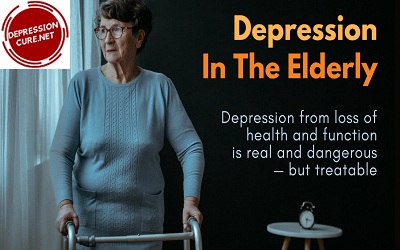

Depression in elderly is treatable, and those who recover from depression have improved physical and social functioning. Unfortunately, older people with clinical depression do not receive adequate treatment.

Clinical depression is common in seniors — about 3% suffer from major depression (see below for definition), but many more from milder forms of clinical depression.

Clinical depression in elderly can lead to disability and increased mortality.

What is depression?

Sometimes we call ourselves “depressed” to describe the sad or down feelings that we all experience at one time or another in the course of life.

If we have a bad day or feel sad over something that has gone wrong in our lives, the mood may pass on its own, or we can distract ourselves or cheer ourselves up.

We can still function well, do what we need to do at work or school, and be there for our loved ones. Typically we can cope with this kind of a down mood without professional help.

In contrast, clinical depression is a persistently sad mood that persists (lasts two weeks or longer) and impairs one?s ability to function in work, home, or social relationships. Clinical depression is a severe medical problem.

A clinically depressed person cannot be cheered up or pull themselves out of it any more than they could pull themselves out of another medical problem such as diabetes or heart disease.

Sometimes the sad mood is apparent; sometimes it takes the form of losing interest and pleasure in usual activities

What is major depression?

Major depression (major depressive disorder, or a major depressive episode) is a term for a clinical depression that meets specific criteria.

It is diagnosed when one has a persistently down mood or loss of interest for two weeks or more and is accompanied by poorer functioning in some critical area of life (such as work, relationships, health). Furthermore, one must have at least 3 of the following symptoms as well:

- A significant decrease (or increase) in appetite or weight

- Insomnia (or excess sleep) nearly every day

- Agitation or retardation (being slowed down), noticeable by others

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feelings of worthlessness or inappropriate guilt

- Diminished ability to think or indecisiveness, or concentrate

- Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide

Depression affects one?s whole body, as well as their mood and thoughts. It affects how one feels about oneself and others.

Major depression can be quite debilitating and even life-threatening, and it usually requires treatment. Someone who is in a significant depression also can feel a great deal of anxiety, worry, and fearfulness. Years ago, the term “nervous breakdown” sometimes was used to describe a significant depression.

Click Here To Read: Depression In Older Adults

What are the causes of depression?

The causes of depression, in terms of the exact changes in brain chemistry and function, are unknown. What is known is that these changes can be triggered by the stresses of certain life events such as illness, childbirth, death of a loved one, life transitions (such as retirement), or interpersonal conflicts.

We also know that some people are at more risk for depression because of family history or previous episodes of depression or anxiety disorders. ?

It may be that the stresses of the depressive symptoms in themselves cause permanent changes in the brain, perpetuating the cycle of depression. The exact nature of these interactions between life events and brain changes is unknown.

Still, we know that the standard treatments, antidepressant medication or psychotherapy, work to resolve the symptoms.

Late-onset depression refers to depression occurring for the first time in an older person (after age 60). In these cases, causes include physical illness and disability (especially due to stroke), grief, and social isolation.

In some cases, late-onset depression is probably caused by small stroke-like damage to areas of the brain involved in mood regulation.

Is a tendency to depression inherited?

Major depression seems to occur in families from one generation to the next so that a strong family history of depression is a risk factor.

However, it is essential to note that many people with depression have no family history whatsoever of psychiatric illness, and many people with strong family histories will never develop a depressive disorder. A family history of depression may be less critical in depression in elderly.

What is the difference between depression and grief?

At the death of a loved one, it is certainly reasonable to feel sad and to withdraw somewhat from one?s usual activities; it is also common to have difficulties with sleep, appetite, and energy.

It is even common to have thoughts about death and to die. These symptoms are similar to those of significant depression, but clinicians do have ways of differentiating between depression and grief.

Usually, a diagnosis of major depression will not be made until two months after the death. However, the diagnosis can be made sooner under some circumstances.

It is common for the bereaved to experience feelings of guilt about what he or she did or did not do at the time of the death, feeling to blame for the death in some way.

However, if the bereaved is exploring a more generalized sense of profound guilt, feeling to blame for things other than the death itself, that person could be in major depression.

Such a person may also be feeling a dramatic loss of self-esteem and worthlessness, feelings that are not common after a death. Another marker of depression is a prolonged or marked functional impairment.

In other words, depression may be present if the bereaved is unable to perform most of his or her usual activities or can no longer socialize with family or friends at all.

Isn’t depression normal in older people?

Major depression is not normal in older people. As with younger people, seniors go through life changes that can often lead to temporary feelings of sadness, which are considered normal.

For example, after the death of a spouse or other loved one, seniors are likely to feel the same symptoms as someone with major depression.

However, sadness that persists is associated with the symptoms of major depression described above, or is accompanied by impairments in everyday function or thoughts of suicide, is not normal.

Click Here To Read: Happy Fathers Day – 15 Ways To Make Your Father Happy

Is depression in elderly treatable?

The excellent news about depression in elderly is that it is treatable, with 60-80% of cases improving with standard treatment.

Treatments for depression in elderly?

Three major types of treatment are proven to help depression in elderly: antidepressant medication, psychotherapy, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

Medication treatment usually starts with a serotonin reuptake inhibitor such as fluoxetine (Prozac), sertraline (Zoloft), paroxetine (Paxil), or citalopram (Celexa). These types of medications are typically well-tolerated; side effects include sexual dysfunction, nausea, sleep problems, diarrhea, or anxiety.

Many, but not all, of these side effects, improve over time. One common problem in the treatment of depression (in all ages) is that medications do not improve symptoms immediately, but take two weeks or more.

During this time, patients are at high risk of stopping taking the drug, perceiving it as having side effects, and not helping. A longer-term view is necessary: these side effects are likely to go away in a few days or weeks, while the improvement of depression with the medication is likely to be long-term.

Other drugs include venlafaxine (Effexor), mirtazapine (Remeron), bupropion (Wellbutrin), and nefazodone (Serzone), which may be suggested because they have a different mechanism of action or are easier to tolerate.

When a doctor prescribes one of these medications for you, it is important to make sure that they are aware of your other medications, to prevent drug interactions.

Psychotherapy is effective for mild to moderate depression in elderly. In this form of treatment, sometimes called “talk therapy,” the patient sees a therapist (who may have a masters’ degree or a Ph.D. or Psy.D. in clinical psychology) or psychiatrist for frequent sessions (often weekly for about an hour).

At these sessions, problem areas in a patient’s life are explored in a way that helps them see things in a more constructive or less depression-associated manner. Some types of psychotherapy are interpersonal therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and problem-solving therapy.

It may be that the combination of antidepressant medication and psychotherapy provides the best hope for recovery from depression.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is typically reserved for severe forms of depression (such as depression that does not respond to medication, or depression associated with altered thinking called psychosis).

It consists of electrically causing a seizure to a patient a total of 6 to 12 times over several weeks. It should be noted that ECT is felt to be safe and highly effective for depression in elderly, and it is well-tolerated by most.

The main side effects are brief confusion after treatment (lasting a few minutes or hours) and temporary disruption of memory (often, people have dim memories of the period they are receiving ECT, though memory before and after the treatment course is unimpaired).

What are the risks of untreated depression in elderly?

Probably the most severe risk of depression in elderly is mortality — depressed elderly are more likely to die, either by suicide or by worsening of medical illness.

It is also known that depressed elders are more disabled than non-depressed elders and that they tend to recover or rehabilitate more poorly from medical diseases such as stroke or hip fracture.

How can I get treated for depression?

It is essential to be treated by a mental health professional under most circumstances. For example, the Depression in elderly Evaluation and Treatment Center can provide evaluations and subsequent treatment, and it also can help with referrals in the community outside of the center.

Another place to start can often be your family doctor. He or she will also be able to help you locate a mental health professional in your area.

A referral to a private psychiatrist, psychologist, or social worker can be found through their respective professional organizations such as the American Psychiatric Association, the American Psychological Association, and the National Association of Social Workers.

Many communities also have geriatric assessment centers, such as the Benedum Geriatric Clinic in the Oakland section of Pittsburgh.

Should I see a mental health professional?

If you feel that you have any of the symptoms of depression, it is an excellent idea to see a mental health professional for an evaluation.

Whether or not you are diagnosed with depression, that professional will be able to help you deal with those symptoms and feel better.

Too many people suffer needlessly when appropriate help is easy to obtain. Depression can become a significant disability and worsen the outcome of major health problems such as heart disease, cancer, and strokes.

What is a geriatric psychiatrist?

A geriatric psychiatrist is a medical doctor who has special interest and training in treating the mental health problems of patients over the age of 60.

These professionals are particularly knowledgeable about the factors that complicate the treatment of depression in older people, such as medical illnesses and the medications that many seniors take to treat those illnesses.

When is it clear than an antidepressant medication is not working? When do you change to a different antidepressant?

Antidepressants often are not effective when they are taken improperly or when one has not been taking an adequate dose for a long enough time.

Antidepressants can take four weeks or more to begin having a positive effect, and this is only if the patient is taking them daily as prescribed.

Often, the dose needs to be raised, and the patient will need to be on that higher dose for four weeks, at a minimum, to know if a particular medication will be useful.

If patients do not feel better after a week or two, they often stop treatment or ask for a change of medication. In this case, they have not given the drug enough time to help them.

If an antidepressant is helping, but only partially, what can be done?

Sometimes a better response can be obtained by raising the dose of the antidepressant. Sometimes another treatment can be added to maximize the response.

If a patient is not receiving psychotherapy, the addition of psychotherapy can help the patient to address his or her life issues that could be sustaining any residual depressive symptoms — in younger adults with chronic depression, the combination of medication and psychotherapy appears to give a higher chance of recovery from depression.

Another possibility is the addition of a second antidepressant, sometimes called “augmentation.” At the Late Life Evaluation and Treatment Center, we often augment serotonin reuptake inhibitors with other medications such as bupropion (Wellbutrin), lithium, or nortriptyline (Pamelor), with a fair rate of success but sometimes with the risk of additional side effects.

Other options include providing psychotherapy along with medication or switching to a drug that works differently, such as venlafaxine (Effexor XR).

How do antidepressants work?

Antidepressant medications seem to work by increasing the levels of neurotransmitters that are available in the brain.

Neurotransmitters are the chemicals that facilitate communication from one neuron to another, allowing information to move along nerve pathways.

Antidepressants do not give people a “high” or make them immediately happy. They have no value on the street, and drug dealers do not push them.

Also, someone taking an antidepressant typically does not lose his or her ability to have feelings or generally respond to emotional events. There is no evidence that these drugs are addictive in the way that alcohol or street drugs are.

Click Here To Read: Top 23 Ways For Raising Children Successfully

I’m being treated for depression, and I feel a lot better. What next?

It is tempting to stop the treatment for depression when one gets better, but in depression in elderly(as well as many other causes of depression), this is not a good idea.

Depression in elderly has a high rate of recurrence, and maintenance treatment with medication or psychotherapy can reduce this chance.

A patient’s story:

Morris pulls himself out of the pool after completing his workout of swimming 54 laps. Just another routine exercise that he has been doing since he was in the 6th grade.

Morris returned to competitive swimming in 1985, competing in the YMCA Masters. He has known the “thrill of victory,” winning national championships in the 50, 100 and 200-yard breaststroke. Morris has also identified the agony of depression.

“I have experienced five episodes of clinical depression. You would think by now I would be able to see them coming.

I guess I don’t want to face going through it one more time, so I will usually tell myself that my loss of appetite and poor sleep patterns are nothing to worry about it.

My wife is the one who picks up on my loss of interest and irritability that often accompanies my episodes. I have never been ashamed or embarrassed to seek treatment once I realize that depression has returned.”

Morris came to the Depression in elderly Evaluation and Treatment Center on the recommendation of a therapist who had treated him for one of his previous episodes of depression. “

I was impressed with the care and attention to detail that the staff showed me right from the beginning. They seemed very confident and optimistic, while I worried that I might never come out of this depression.”

The combination of psychotherapy, medication, and tender loving care from the entire Depression in elderly Evaluation and Treatment Center staff proved to be all that Morris needed to return to his active and engaged lifestyle.

In addition to his competitive swimming, Morris leads the Senior Men’s Fellowship discussion group at his temple. He and his wife are co-producers and co-hosts of a local cable television show, “More Than Just Learning,” now in its 12th year of production.

“It’s very discouraging to face another episode of depression, but it’s also very heartening to know that there are effective treatments. I wouldn?t hesitate to recommend seeking help for depression to anyone who is suffering from it.”

Click Here To Read: Irritability

Ten Myths about Depression in Elderly

Myth 1: “Depression is normal in older people.”

Fact: While a short period (hours or days) of depression may occur in many older people, depression lasting weeks or months only occurs in a small percentage. It is not an inevitable part of aging.

Myth 2: “Of course I’m depressed; wouldn’t you be if you were sick (or disabled)?”

Fact: Older people with chronic illness and disability are indeed more likely to be depressed. But this does not mean that depression is normal or inevitable in this context.

The good news is that depression in medically ill people is just as treatable as that is medically well people.

Myth 3: “I can pull myself (or my spouse) out of it.”

Fact: we can get ourselves out of very mild forms of depression, like brief periods of low mood or sadness, without professional help. But clinical depression, or major depression, requires professional advice.

Myth 4: “Only crazy people see a psychiatrist (or psychologist or therapist).”

Fact: the vast majority of older people who seek mental health care are suffering from depression. Psychiatrists or others do not use the term “crazy” in mental health for many reasons, but mainly because of the negative image that such a word conjures up.

Myth 5: “Medicine for depression will make me a zombie.”

Fact: The most commonly-prescribed antidepressants have little or no sedative effect. Antidepressants do not change your personality or make you “a different person.” They reduce or improve symptoms such as sadness, anxiety, low energy, and poor sleep.

Myth 6: “I’m too old to change.”

Fact: the likelihood of improving from depression (with appropriate and adequate treatment) does not appear to decrease with age, although there is little research about this in the very old (age 75 and older).

Myth 7: “The last thing I need is another pill.”

Fact: often, people are taking many pills because they are physically sicker because of depression; treatment of depression can reduce overall medication use.

Many antidepressant medications can be considered as a single pill, once per day. Finally, psychotherapy is also useful for late-life depression.

Myth 8: “I can’t get treatment for depression right now; I have to focus on getting better from my medical problem.”

Fact: if you are depressed and medically ill, one of the most critical parts of getting better from your medical problem is to get help for your depression.

We know that depression amplifies medical illnesses such as heart disease and cerebrovascular disease (stroke), leading to more significant disability and mortality.

Myth 9: “I don’t have time to deal with depression because I need all my energy to care for my spouse (or parent, child).”

Fact: if you are depressed, you need to get better to best care for your loved one. A good analogy is a heart: it provides blood to the entire body, but first, it provides itself with blood.

Myth 10: “An antidepressant medicine wouldn’t be safe for me because I have heart disease (or kidney or liver problems, cancer, stroke).”

Fact: most antidepressant medications are safe even with severe heart, kidney, liver, brain, or another organ disease. On the contrary, in the case of heart disease, we know that untreated depression is very dangerous.

The Depression in elderly Evaluation and Treatment Center is part of a federally-funded research center. We have been conducting clinical research on depression in older people since the mid-1980s.

This center is recognized as one of the premier research centers in the area of late-life depression. Here are some of our most important research findings:

- Depression in older adults is treatable. We have found, in several treatment studies of medications, alone or in combination with psychotherapy, a high rate of recovery from depression. Typically 50% or more of individuals will respond (improve) on the first antidepressant medication tried. However, for those who do not respond initially, strategies to augment medication have produced recovery rates as high as 80%.

- Older adults who recover from depression with treatment are more likely to stay well if they continue to receive the treatment. However, adults aged 70 and older appear to have a particularly “brittle” response; that is, they have a high rate of relapse (return) of depression despite adequate treatment. We are currently examining this phenomenon in an ongoing study.

- Older adults with depression AND anxiety have more severe illness in terms of poorer social function, greater severity of symptoms, and more thoughts of suicide. We have found that these individuals appear to respond well to standard treatment for depression.

More relevant findings from our research center will be added in the near future.

Note: Depression Cure does not provide any type of medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.